Decarbonization Needs to Hit Closer to Home

April 02, 2024 | By Jacob Plotkin and Rives Taylor

The impacts of climate change are already being felt around the world. Of the nearly 10,000 respondents to Gensler’s Global Climate Action Survey 2023, 90% were recently impacted by severe weather events. High temperatures, irregular precipitation and other extreme weather events are giving rise to a worldwide well-being crisis. Of those affected by severe weather, 60% report negative physical health impacts, 61% mental health impacts, and 70% financial impacts. One in four believe they will be forced to move in the next five years due to environmental issues. Something must be done.

While there is no single culprit, the built environment — the places where we live and work — is a significant contributor to climate change, estimated to make up about 40% of annual CO2 emissions. This figure presents both a challenge and an obligation for the design industry as we help to lead the fight against an ever-escalating climate crisis.

Quantifying the carbon cost of building types

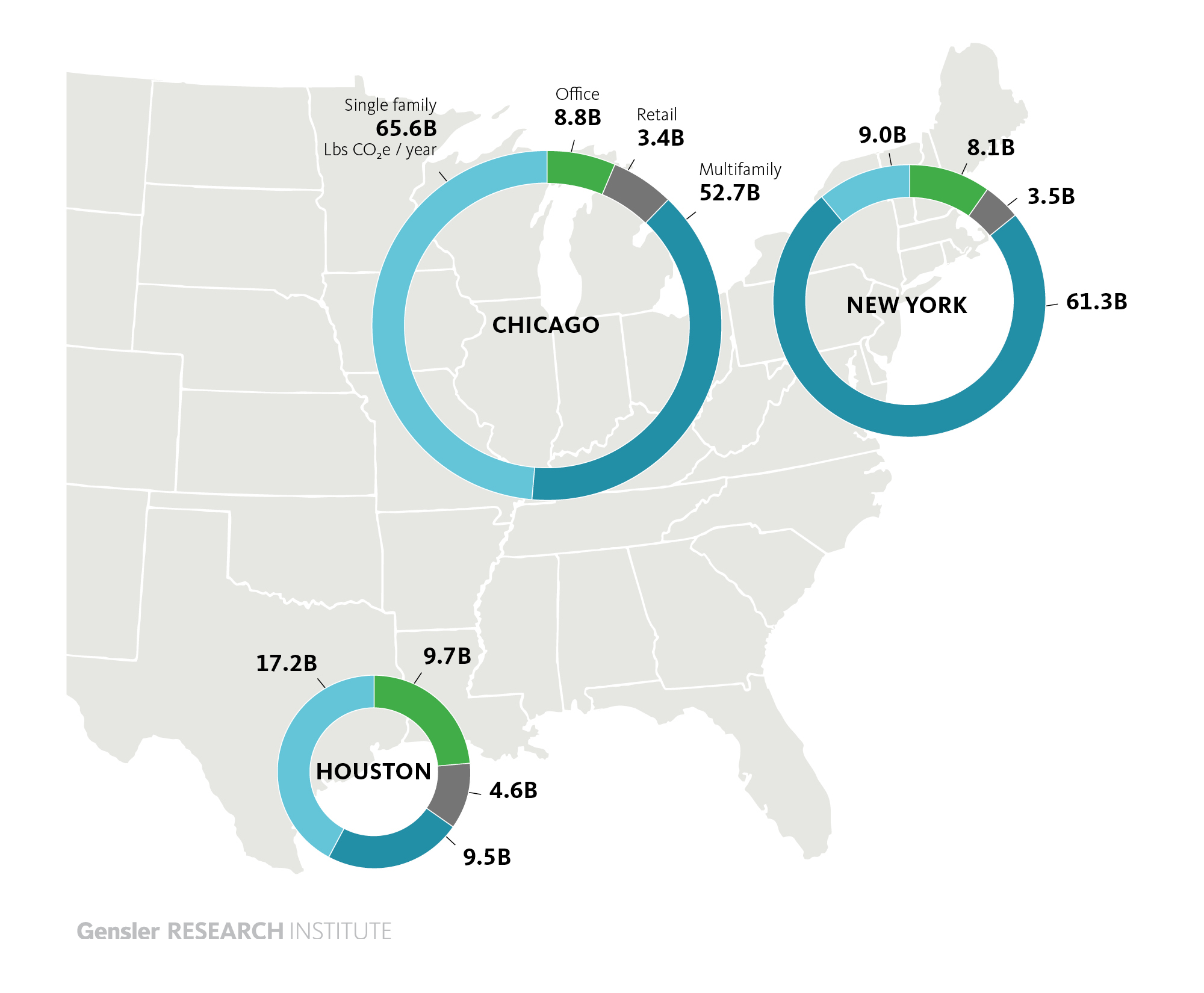

To help discover opportunities for carbon reduction, the Gensler Research Institute’s Center for Resilience Research dug deeper into the carbon emissions associated with the built environment to discover where exactly these emissions are coming from.

Our team’s research explored operational energy use (the energy used to light, heat, cool, and operate buildings) in three major U.S. cities – New York, Chicago, and Houston. We found that while equipment-heavy spaces like data centers and restaurants use a lot of energy per square foot, they also represent a very small proportion of total city square footage.

This means that, at scale, commercial buildings make a relatively small impact on total citywide carbon emissions. Homes on the other hand, both single family and multifamily, can constitute up to 75% of a city’s built environment. While one house emits less carbon than one office building, the total footprint of residential buildings makes homes our biggest carbon challenge.

Despite the amount of space and carbon devoted to our homes, we can too often treat the cost of operating residences as a given while looking elsewhere for ways to save. But if cities want to get serious about reducing their carbon impact, exploring ways to reduce emissions at home is a key opportunity.

Opportunities to reduce home emissions

There are many ways that individuals can reduce their home emissions. This includes installing better insulation, upgrading HVAC systems, and buying more efficient appliances. Of course, each of these does come with a cost implication. Policy support and incentives exist to ease this transition, but more time is needed for full implementation. Instead, here and now, there is a free solution for reducing carbon emissions: behavioral change.

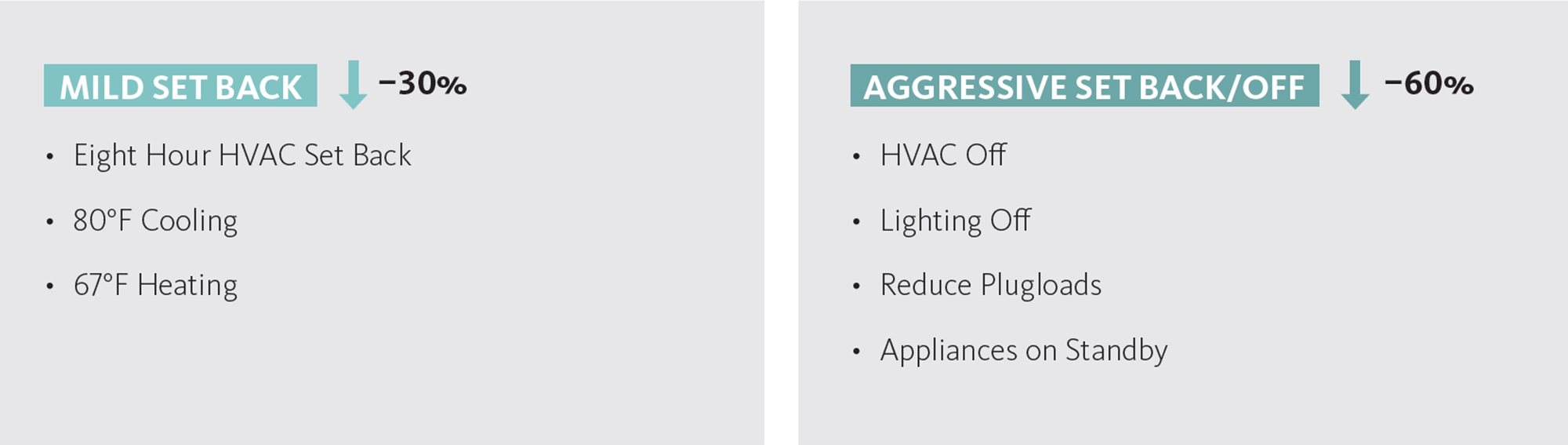

Our analyses revealed a crucial opportunity to reduce residential emissions: setting back the home when it is unoccupied. We identified two forms of setbacks: a mild setback that reduces emissions by 30%, and an aggressive setback that reduces emissions by 60%. Through simple behavioral shifts, like adjusting thermostats, lighting, and appliance use, we can eliminate an incredible portion of a city’s daily carbon emissions.

These setbacks are most effective when the home is unoccupied. So, are that many homes empty during the day? Gensler’s City Pulse 2023 data estimates that approximately one-third of homes could be vacant during a given workday, presenting incredible opportunities for at-home energy use setbacks.

The office therefore represents the perfect opportunity for people to get out of their homes and open the potential for home setbacks. Individual savings achieved by setting back residences typically surpass those emission savings from eliminating commutes and office operations for the same day, making it more carbon efficient in most cities to work in an office than from home. Simple behavioral changes like this could be an impactful starting point for reducing our collective carbon impact.

For media inquiries, email .